The threat posed to society by disinformation in the age of social media is rapidly becoming a primary concern for policymakers. NATO allies are struggling to find ways to effectively resist state-backed Russian disinformation campaigns in eastern Europe, as tensions over Ukraine continue to escalate. The emergence of the Metaverse poses a thorny problem to regulators, and misinformation about vaccines continues to hamper the booster program in this country. All things considered, the UK government’s Online Safety Bill looks set to face some serious challenges before it is passed by parliament. Recognising the immense topicality of this issue, a panel of experts from academia and government met recently in an online colloquium hosted by History and Policy from London University’s School of Advanced Study, in order to discuss the nature of the threat posed by disinformation.

The Proportions of the Problem

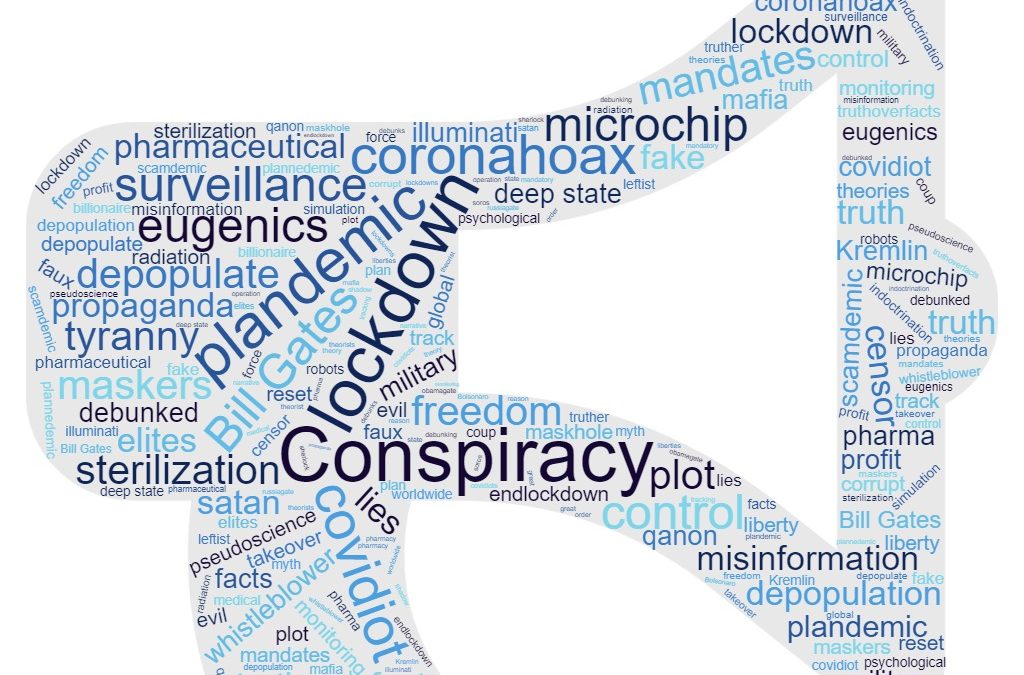

There is a wide spectrum in the quality of the information circulating online, from factual information with verified sources, to misinformation (misleading information unintentionally presented as fact), to disinformation (false information that is deliberately spread). Of these, the latter is particularly pernicious as it is designed to maximise disunity and distrust within the targeted society and has been increasingly deployed by authoritarian regimes over the last few years. Russia has been especially active in spreading disinformation in Europe and the US, for instance proposing thirty-five different explanations for the poisoning of Sergei Skripal in 2018 and fuelling the already polarising process of US elections. More recently, the state-sponsored media outlet Russia Today (RT), has sought to undermine confidence in the UK government’s Covid measures.

However, we cannot blame the rise of disinformation during the past few years on foreign actors alone. There are numerous domestic sources of misinformation and disinformation which have sought to capitalise on people’s misgivings about the pandemic by selling a variety of products and services online. Nor is this a uniquely modern problem, as misinformation and disinformation in times of public crisis have a long historical pedigree. This can be seen for example in the stories that emerged in response to the plague in Europe, and fears about the side-effects of Smallpox vaccination in Victorian England. This brings us to consider the narrative manifestations of misinformation: conspiracy theories. While the dynamics of the information sphere have undoubtedly shifted with the advent of social media which has rendered conspiracies much more visible than before, the levels of belief in conspiracies have changed comparatively little over time. Researchers have long pondered why these misleading narratives remain so consistently seductive to a certain portion of the population.

The Sociology of Conspiracy

Political scientists and sociologists are often baffled by the demography of believers in conspiracy theories, as they defy simple characterisation by gender, age or political perspective. Similarly, psychologists have struggled to delineate the psychology of a conspiracist. In light of this, it seems difficult to justify the pathologizing of conspiracy theorists with terms like ‘infodemic’ and projects aimed at ‘inoculating’ against disinformation. Instead, we might reflect that we all share, to a greater or lesser extent, the desire to make sense of the world with overarching explanatory narratives, which some people derive from religion, others from politics, and others from conspiracy theories.

Historically we can also see the centrality of sense-making in people’s lives, as the desire to overcome the vulnerability experienced in the face of nature’s random acts of violence, gives rise to fantasies about the forms of agency that cause and cure disease, for example. Thus, crises like the Covid pandemic have the capacity to forge diverse coalitions of people, unified by their distrust in the authorities, and vague, visceral feelings about security or liberty. These nascent populist movements have their historical counterparts as well, particularly in Europe in the 1930s.

Multiple Sources and Multiple Strategies

No matter how concerning the threat posed by disinformation may be, especially when it taps into long-term conspiracies and popular resentments, there is no single solution. Instead, the UK government has adopted multiple strategies, with coordination between the Home Office, the Foreign Office, DCMS and the Cabinet Office. The counter-disinformation capabilities that the government currently wields, include campaigns like Don’t Feed the Beast and Look Into Their Eyes, the RESIST toolkit, fact-checking and debunking websites, content removal in tandem with social media companies, rapid response units to deal with disinformation that poses a national security threat, and efforts to increase media literacy among the young and vulnerable.

As is evident from the above, it takes multiple approaches to deal with the many-headed hydra that is disinformation and misinformation in the public sphere. While some research suggests that democratic governments should take the offensive in combating this problem, for now at least, the government’s efforts remain largely defensive and reactive. As one panellist pointed out, “the truth may take longer, but in the end, it counts for more.”

Behavioural Science in Countering Disinformation

Government approaches to counter-disinformation that rely on behavioural science have provoked particularly strong debates. For instance, behavioural economist Richard Thaler’s so-called Nudge Theory has informed measures that seek to secure behavioural compliance through indirect and covert suggestion. Nudge tactics have their place in a spectrum of strategies for protecting the public, that range from subtle suggestions, to ‘shove tactics’ that include explicit recommendations, regulation and enforcement.

It is questionable whether the government’s use of tactics that are necessarily covert can ever truly be called transparent or accountable, and using such approaches risks fuelling the very conspiracies about elite rule and brainwashing that counter-disinformation efforts seek to mitigate. On the other hand, it is difficult to justify abolishing techniques informed by behavioural psychology when one considers that they are being deployed for the public good, on projects that measure their success in the numbers of lives saved.

The Importance of Trust

The main unifying factor behind recent and historical blooms of disinformation and conspiracy it is a deficit of trust, whether in technology companies, pharmaceutical companies, healthcare systems or governments. While it is quite natural to seek certainties in such an uncertain world, it is the lack of trust that civil servants are truly serving the public’s best interests that leads people to find alternative answers in conspiracy and misinformation. When people can trust their institutions, representatives, and healthcare workers, then they can outsource much of the time-sensitive decision making in a crisis to the experts and professionals, but without this key ingredient, people resort to their own decisions and are invariably informationally ill-equipped to do so. Thus, rather than pathologizing conspiracists, there is a need to address the underlying issue of distrust.

However, it is understandably difficult for certain groups to have blind faith in the medical establishment, given the various abuses carried out by medical authorities in the twentieth century, from eugenics programs to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. It is critical to distinguish, therefore, between antivaxxers and the vaccine hesitant, and to exercise empathy and understanding in persuading people to make good decisions, rather than castigating their caution and further alienating them. In summary, an empathetic approach that restores public trust in our institutions offers us the greatest chance of reducing the harmful effects of disinformation and conspiracy in the future.

Recent Comments